Phaethon heeft een diameter van circa 5 km

Phaethon is bijzonder. Het is namelijk waarschijnlijk een uitgedoofde komeet. Hij heeft bijna de exacte baan als de Geminiden meteorenzwerm en wordt dan ook aangezien als de bron van deze zwerm.

Phaethon behoort tot de groep Apollo- planetoïden.

De Apollo-planetoïden zijn een groep planetoïden genoemd naar de eerst ontdekte Apollo-planetoïde: (1862) Apollo. De banen van de Apollo-planetoïden kruisen de aardbaan: ze hebben een elliptische omloopbaan waarvan de halve hoofdas groter is dan deze van de aarde. Sommige kunnen zeer dicht tegen de aarde komen, waardoor ze een potentieel gevaar vormen voor de aarde (zie aardscheerder). Hoe dichter de waarde van de halve hoofdas van de planetoïde de waarde van de halve hoofdas van de aarde is, hoe kleiner de excentriciteit van de omloopbanen moet zijn om te kruisen. Waarschijnlijk stortte een planetoïde van de Apollo-groep neer van zeventien meter in de Russische stad Tsjeljabinsk op 15 februari 2013.

De grootste bekende Apollo-planetoïde is (1866) Sisyphus, met een diameter van ongeveer 8,5 kilometer. De lijst van de Apollo-planetoïden wordt continu bijgehouden. Op 4 december 2004 waren 1487 Apollo-planetoïden bekend.

Bron: http://wikipedia.org

What’ll happen when 3200 Phaethon sweeps past Earth?

This mysterious rock-comet is the parent body of this week’s Geminid meteor shower. It’ll brush closely past Earth on December 16, just a few nights after the Geminids’ peak. Will 2017 be a fantastic year for the Geminids?

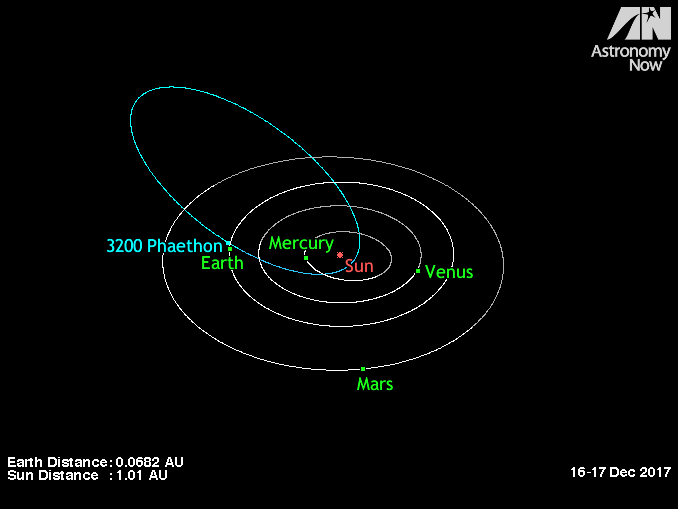

3200 Phaethon will sweep close to Earth – just 0.069 astronomical units (6.4 million miles, 10.3 million km, 26 lunar-distances) on December 16, 2017 at 23 UTC; translate to your time zone. Image via Osamu Ajiki (AstroArts)/ Ron Baalke (JPL) / Ade Ashford (AN)/ AstronomyNow. It will not be visible to the eye.

On the peak mornings of the 2017 Geminid meteor shower – December 13 and 14 – the moon will be in a waning crescent phase, visible only shortly before dawn, and near two planets before dawn. Even more importantly, a curious body known as 3200 Phaethon – sometimes called a rock-comet, thought to be the source of the Geminid meteor shower – will be gliding through space relatively near to Earth. It’ll come closest to Earth in its 523.5-day orbit only a few days after the Geminids’ peak, on December 16.

What will happen? No one knows for sure how many meteors you might see, or if 2017’s shower will be extra special because 3200 Phaethon is nearby. But it’s a fact that, when a parent comet is nearby, a meteor shower can be spectacular.

So plan to watch this shower in 2017!

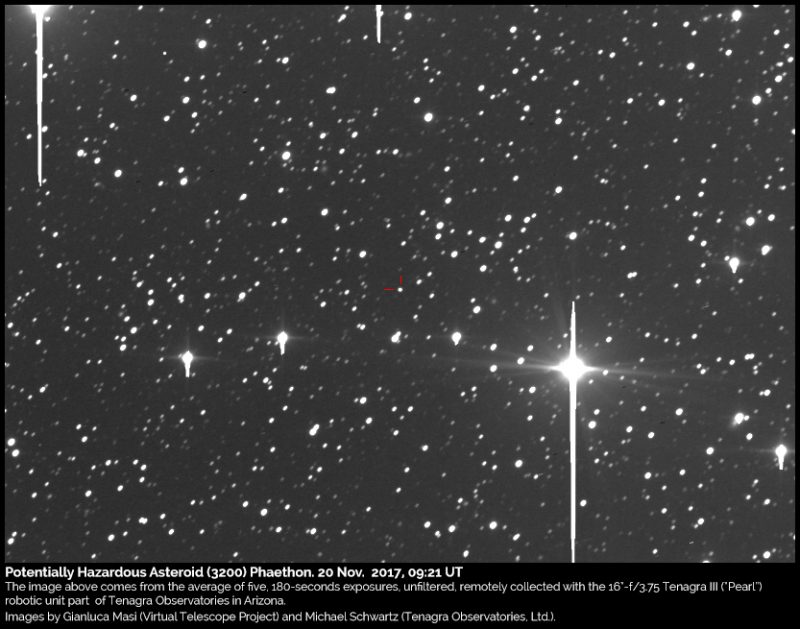

The object 3200 Phaethon is located between the red tick marks at the center of this photo. Image acquired November 20, 2017 by Gianluca Masi of the Virtual Telescope Project. Gian will be hosting an online view of 3200 Phaethon.

3200 Phaethon is a very interesting and mysterious object. It was one of the first known bodies in space that blurred the distinction between asteroids and comets. All the other meteors in annual showers are known to be icy debris left behind by comets, after all, but the Geminids are known to come from this strange asteroid-comet hybrid, which some call a rock-comet.

Asteroids are rockier, or more metallic, than comets. Their orbits tend to be more circular, while comets tend to have more elongated orbits. 3200 Phaethon, with its asteroid name, has an orbit that more closely resembles that of a comet than an asteroid. It also has mysterious ejections of dust, and dust tails, and astronomers have said it’s possible that the sun’s heat causes fractures on the surface of 3200 Phaethon, similar to mudcracks in a dry lake bed.

This closeup of an image of 3200 Phaethon by NASA’s STEREO A spacecraft shows a tail extending faintly toward lower left. Image via NASA/ SkyandTelescope.com.

3200 Phaethon was the first asteroid to be discovered via spacecraft on October 11, 1983. Astronomers Simon F. Green and John K. Davies noticed it while searching Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) data for moving objects. Charles T. Kowal confirmed it optically and said it was asteroid-like in appearance. The object received the provisional designation 1983 TB. Two years later, in 1985, using the convention for naming asteroids, astronomers assigned it its number and name: 3200 Phaethon.

An interesting feature of the orbit of 3200 Phaethon is that it comes very close to the sun, closer than any other named asteroid (though there are numerous unnamed asteroids that do sweep closer to the sun). That’s why it was given the name Phaethon, for the mythological son of the Greek sun god Helios.

Today, it’s classified as a potentially hazardous asteroid, which doesn’t mean it’s a threat to Earth. It just means two things. First, 3200 Phaethon is big – about 3 miles (5 km) wide – big enough to cause significant regional damage if it were to strike Earth. Second, it’s known to make periodic close approaches to Earth. A “close approach” in 2017 means 26 times farther than the moon. And, by the way, the orbit of 3200 Phaethon is exceedingly well studied, and astronomers know of no upcoming strike by this object in this foreseeable future.

In fact, in December 2017 – according to NASA NEO Earth Close Approaches – there are no fewer than 30 objects that’ll come closer than 3200 Phaethon. The closest of these will be 2017 WV12, a 20- to 40-meter-wide object that’s miss us by about a million miles (1.6 million km) on December 9.

The composition of 3200 Phaethon resembles that of asteroid 2 Pallas. Both are dark, B-type asteroids comprised of materials that have been modified by water. The first in this series of Hubble images is marked with the asteroid’s spin axis (top) and south pole. Image via B. E. Schmidt et. all / NASA / ESA/ SkyandTelescope.com.

On the peak nights of the 2017 Geminid meteor shower – nights of December 12 and 13, mornings of December 13 and 14 – the meteors will be radiating from near the star Castor in Gemini. On those nights, 3200 Phaethon won’t be far from Gemini on the sky’s dome. It’ll sweeping across a neighboring constellation, Perseus the Hero. Will you be able to see it with the eye? Not even kinda. Its magnitude is predicted to be around +10.7, making it far too faint to see with the eye alone.

Telescope users will be following 3200 Phaethon, however.

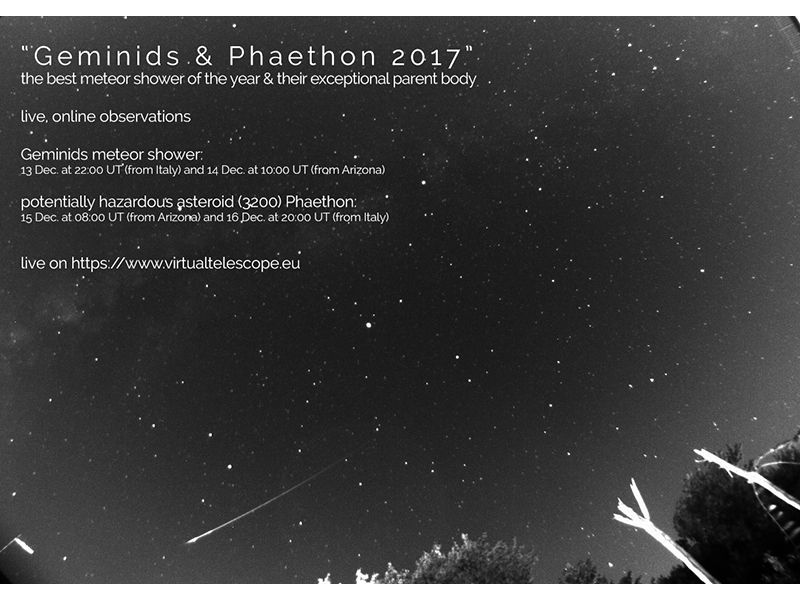

And don’t forget to watch for 3200 Phaethon online:

https://www.virtualtelescope.eu/2017/11/20/geminids-2017-meteor-shower-online-observation-13-14-dec-2017/

The Virtual Telescope Project will be offering online viewing this year of both the Geminids and 3200 Phaethon. Check out the times listed in the poster above. Click here to translate to your time zone. Click here to go to Virtual Telescope Project’s site.

Bottom line: 3200 Phaethon will brush relatively close to Earth on December 16, just a few nights after the peak of the 2017 Geminid meteor shower. Will 2017 be a fantastic year for the Geminids?

Bron: http://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/rock-comet-3200-phaethon-geminid-meteor-shower

Asteroid 3200 Phaethon: Geminid Parent at Its Closest and Brightest!

The parent asteroid of December's Geminid meteor shower, 3200 Phaethon, is about to make a historically close flyby. Get ready to watch it race across the sky.

The orbit of asteroid 3200 Phaethon is highly elongated, much like a comet's. Perhaps it is an extinct comet, or maybe it's a true asteroid that's cracking and shedding rocky bits when closest to the Sun. The 5.1-kilometer-wide Phaethon completes an orbit every 1.4 years.

Sky & Telescope diagram

We have a fantastic opportunity to see a unique asteroid brighter than it's ever been observed. 3200 Phaethon (FAY-eh-thon), the size of a rural hamlet, will pass within 10.3 million kilometers from Earth at 6 p.m. Eastern Time (23:00 UT) on December 16th. Just before closest approach, it will reach magnitude 10.7, bright enough to track in a 3-inch telescope. And I do mean track. Hold onto your eyepiece! This thing will be scooting along at up 15° per day or 38″a minute (about the distance between Albireo and its companion star) — fast enough to cross the field of view like a slow-moving satellite.

Whenever I see an asteroid or comet move in real time, I'm reminded of a particular 10-km-wide rock that slammed into the Yucatan 65 million years ago and led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. To a T. rex with a telescope, the coming nemesis would have looked like an innocent pinprick of light the night before, inching across the stars just like Phaethon will for us. Only in this instance, we needn't worry about an impact. While classified as a potentially hazardous asteroid, a look ahead shows that Phaeton will keep a safe distance for at least the next four hundred years.

This diagram gives an overview of 3200 Phaethon's flight from Auriga through Capricornus in the next few weeks. Its changing phase is shown throughout. Numbers beneath the phases are visual magnitudes at the time. One reason the asteroid fades so rapidly after closest approach is because its phase narrows to a crescent from our perspective. Asteroid size is not to scale.

Tom Ruen, with additions by the author

Phaethon distinguishes itself in other ways. It comes closer to the Sun than any other named asteroid, with a perihelion distance of 0.14 AU, or less than half that of Mercury. If lead melts on the innermost planet, where the temperature reaches 800°F (427°C), Phaethon's got it beat by a mile. Its scorched surface tops out around 1200°F (627°C), hot enough for lead to flow like water and aluminum to turn to putty.

Getting roasted by the Sun every 524 days explains Phaethon's other claim to fame as the parent of the Geminid meteor shower. Shortly after it was discovered on October 11, 1983, with the orbiting Infrared Astronomical Telescope (IRAS), American astronomer and comet researcher Fred Whipplenoticed that Phaethon's orbit matched that of the Geminids, clinching it as the shower's source.

Compositionally, 3200 Phaethon resembles the larger asteroid 2 Pallas and may possibly be related to it. Both are dark, B-type asteroids comprised of materials that have been modified by water. The first in this series of Hubble images is marked with the asteroid's spin axis (top) and south pole.

B. E. Schmidt et. all / NASA / ESA

Most meteor showers originate with comets. When a comet gets near the Sun, solar heating vaporizes dust-rich ice from its nucleus, and the push of sunlight (radiation pressure) blows it back to form a coma and tail. The ejected material forms a trail or stream along the comet's orbit; when the Earth slices through it, the dust slams into the atmosphere and vaporizes, particle by particle, in a meteor shower.

So how do you get dust from an asteroid? An early hypothesis, now discarded, posited that Phaethon might have ice beneath its surface that vaporizes around the time of perihelion. Sounds plausible, but measurements show the asteroid gets too hot for ice to survive either inside or out. Still, you might get blood from a turnip if that turnip is composed of carbonaceous (carbon- and water-rich) minerals like our friend 3200 Phaethon and heated to a temperature high enough to cause the material to break down, crack, and crumble into dust.

This closeup of an image of 3200 Phaethon by NASA's STEREO A spacecraft shows a tail extending faintly toward lower left.

NASA

If Phaethon was once a traditional comet, it is no longer. These days, it's considered a rock comet. a rare type of object that outgasses rock particles instead of ice.

When you pour boiling water on cold glass, the glass shatters from thermal shock. Similarly, extreme solar heating at the time of perihelion causes rapid expansion of Phaethon's crustal rocks. They fracture and release dust that's carried away by the radiation pressure of sunlight. Experiments have shown that the dust particles are about a millimeter across, approximately the size of the Geminids.

For a brief time during the 2009 perihelion, astronomers recorded a surprise doubling in the asteroid's brightness, likely caused by one of these gritty outbursts. Yet questions remain. A meteor shower requires constant nourishment from its parent to put on a show year after year, decade after decade. Astronomers estimate that to maintain a steady supply of meteor dust, Phaethon would have to flare 10 times as often as observed. Does it shed its skin out of sight, when its in the harsh glare of perihelic sunlight?

Whatever's going on, we're going to have a bang-up December. Not only will Phaethon be brighter than ever, but its appearance coincides with the December 13–14 peak of the annual Geminid meteor shower — a rare pairing! We'll have more on the Geminids next week. For now, our job will be to find and follow this exciting asteroid.

Yes, it's crowded! This map shows the track of 3200 Phaethon from December 6–9, 2017, with positions marked at 0 UT (7 p.m. EST the evening before) and stars plotted to magnitude 13. Click to enlarge and then print out for use at the telescope.

SkyMap

From November 29th through December 3rd, Phaethon brightens from magnitude 14 to 13, but does so handicapped by the glare of the nearly full Moon. Luckily, the Moon's out of the way starting on the 5th, when Phaethon will have reached magnitude 12.6 and be within range of a 6-inch or larger telescope. When brightest from December 12–15, it shines between magnitude 10.7 and 10.9. Because we're seeing the asteroid in full or nearly full phase, Phaethon stays relatively bright for many nights prior and up to closest approach. Soon after, it fades as its phase from our perspective thins to a crescent. By December 19th, it drops back to 13th magnitude and then to 15th magnitude on December 21st.

This chart tracks Phaethon from December 9–11 starting at 0 UT. Having Capella nearby is a bonus.

SkyMap

Phaethon spins once on its axis every 3.6 hours with a +0.4-magnitude variation in brightness that patient observers may be able to detect. Visual observers and astrophotographers should also be on the lookout for brightness flares or the potential appearance of a coma.

With Phaethon's speed and brightness increasing, tick marks are shown for every hour on December 11–12. Stars here are plotted to magnitude 11.5.

SkyMap

Our maps will take you through December 17th. I apologize for their number, but Phaethon covers a lot of ground through a star-rich Milky Way, making detailed maps a necessity. I encourage you to create your own personalized charts, easy to do with sky-mapping programs like Stellarium, MegaStar, and Starry Night. For step-by-step instructions, scroll to the end of this earlier blog.

This radar image, made in December 2007 by the Arecibo dish in Puerto Rico, is the best image we have of Phaethon for the moment.

Arecibo / Cornell

NASA's 70-meter Goldstone dish will make good use of this apparition to obtain the clearest pictures yet showing Phaethon's shape and surface features by bouncing radio waves off the object and constructing images based on return echoes. Observations are scheduled for 10 days between December 11–21.

If you don't own a telescope and still want a peek at the asteroid, watch it live on Gianluca Masi's Virtual Telescope Project website at these times: December 15th from Arizona starting at 09:00 UT and December 16th from Italy starting at 20:00 UT.

Try to catch Phaethon now because it won't get this bright again until December 2093, when it will pass within 0.02 AU of Earth and brighten to magnitude 9.4.

Additional charts for tracking Phaethon through December 17th:

December 12–13

December 13–14

December 14–16 (color, B&W)

December 15–17 (color, B&W)

Bron: http://www.skyandtelescope.com/observing/3200-phaethon/

Op 16 december passeert Planetoïde Phaethon 3200 de aarde op 10 miljoen km afstand

Op 16 december passeert Planetoïde Phaethon 3200 de aarde op 10 miljoen km afstand