Cassini-missie maakt zich op voor grote finale

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Credit: NASA/JPL-CaltechDe Cassini-sonde van NASA, die al sinds 2004 rond Saturnus draait, gaat nu echt de laatste fase van zijn bestaan in. Op dit moment wordt de laatste hand gelegd aan een nieuwe serie instructies, die op 11 april naar de sonde wordt gestuurd. Vervolgens brengt de sonde op 22 april een laatste nabij bezoek aan de maan Titan en gebruikt dan de zwaartekracht van deze maan om zijn baan te veranderen. Zijn nieuwe baan brengt de sonde dichter bij de planeet dan ooit te voren. Op 26 april duikt de sonde namelijk voor het eerst tussen Saturnus en zijn ringen door, een opening van zo'n 2400 km. De opening tussen de ringen en de planeet is waarschijnlijk niet helemaal leeg, maar bevat vermoedelijk geen deeltjes die groot genoeg zijn om schade aan te richten aan de sonde. Maar tijdens deze eerste nauwe passage gebruikt men de grote antenne als schild en hoopt men te kunnen bepalen hoe veilig het is om hier daadwerkelijk waarnemingen te doen tijdens de latere passages. In totaal komen er 22 van deze passages en men hoopt nog veel te kunnen leren over deze nabije omgeving van Saturnus. In september zal een verre passage van Titan worden gebruikt om de baan een laatste keer aan te passen. Na twintig jaar is de brandstof van Cassini vrijwel op. De baan wordt daarom zo aangepast dat de sonde op 15 september in de atmosfeer van Saturnus duikt. Tot het allerlaatst zullen daarbij metingen worden verricht en naar de aarde worden gestuurd. (EM)

Meer informatie:

→ NASA's Cassini Mission Prepares for 'Grand Finale' at Saturn

Bron: http://astronieuws.nl/

Over een paar uurtjes gaat het gebeuren: rond elf uur Nederlandse tijd duikt Cassini in het smalle gat tussen de ringen van Saturnus. Het is het laatste en misschien wel spannendste hoofdstuk uit een ruimtemissie die al bijna 20 jaar duurt.

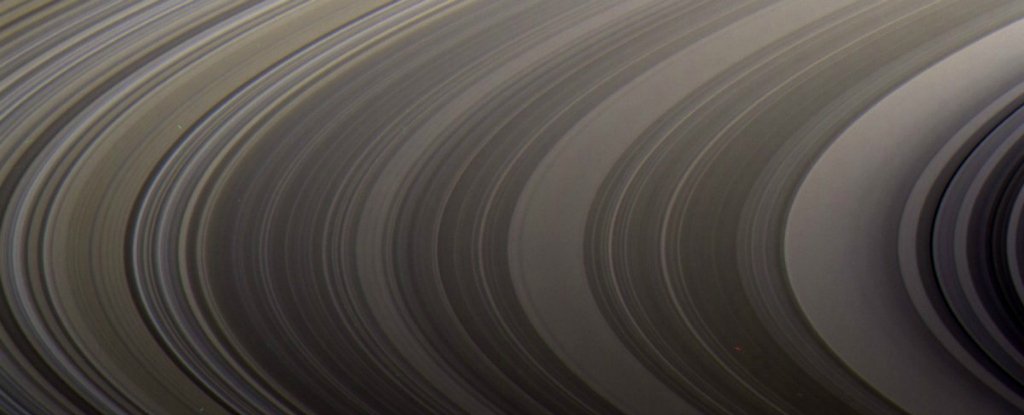

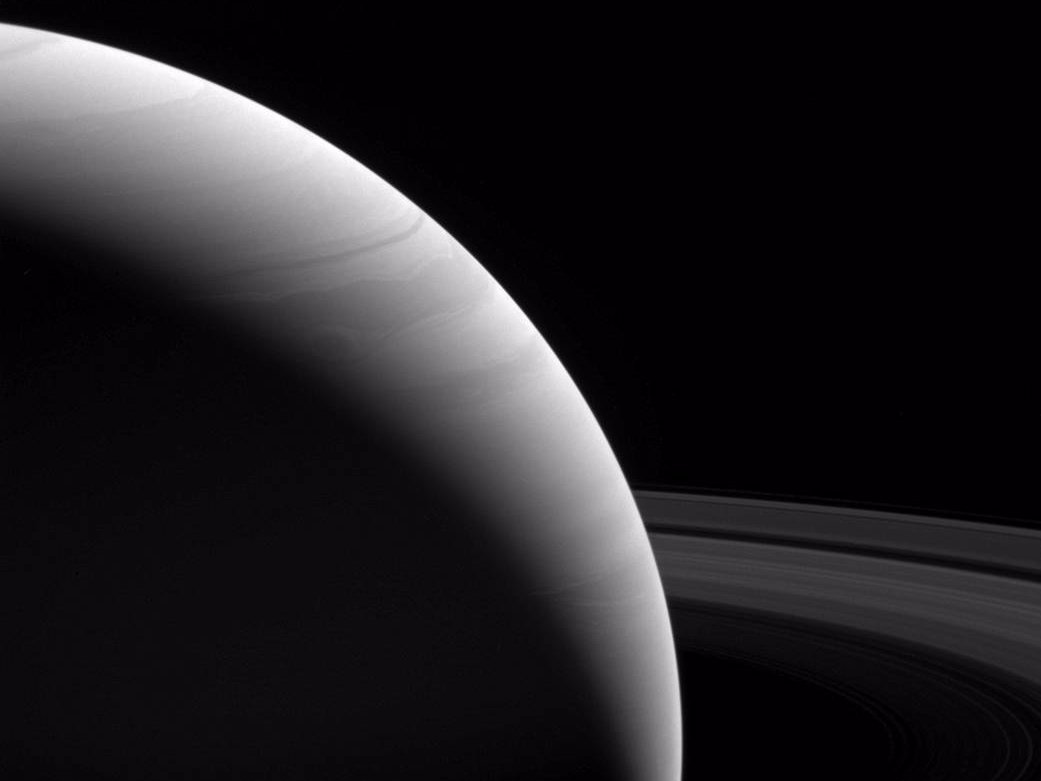

Saturnus en zijn ringen

In totaal zal Cassini 22 keer in de ruimte tussen Saturnus en zijn ringen duiken. De ene keer zal de sonde daarbij naar Saturnus kijken, terwijl de andere keer de blik gericht is op de ringen. Het zal naar verwachting spectaculaire close-upfoto’s opleveren van Saturnus’ wolkendek en de binnenste ringen van de gasreus.

De wetenschap

Maar behalve foto’s verwachten onderzoekers ook veel meer over Saturnus te weten te komen. Zo kan de ruimtesonde tijdens dit deel van de missie de zwaartekracht en magnetische velden van de gasreus nauwgezet in kaart brengen en komen we wellicht eindelijk te weten hoe snel Saturnus roteert. Tegelijkertijd hopen onderzoekers te achterhalen hoeveel materie er in de ringen van Saturnus huist en op basis daarvan meer duidelijkheid te kunnen geven over de oorsprong van die ringen.

Is het gevaarlijk?

Nog nooit heeft een ruimtevaartuig het gebied waarin Cassini zich vanmorgen begeeft, bezocht. Natuurlijk heeft NASA voorafgaand aan die eerste duik heel wat risicoanalyses uitgevoerd, maar het is zeker niet onmogelijk dat Cassini tijdens dit deel van de missie op een onaangename verrassing stuit. Dat is ook de reden dat NASA dit avontuur pas aangaat nu het einde van Cassini’s werkzame leven er bijna opzit (zie kader).

Op het moment dat Cassini in de ruimte tussen Saturnus en zijn ringen duikt – een gat dat zo’n 2400 kilometer groot is – is er geen contact met de aarde. De radiostilte duurt bijna 24 uur: naar verwachting zal de sonde op zijn vroegst op 27 april rond een uur of elf (Nederlandse tijd) weer contact leggen met de aarde. Kort daarna zal de sonde ook de data en foto’s richting de aarde sturen.

Via: https://www.scientias.nl/ruimtesonde-cassini-werpt-zich-vandaag-gat-saturnus-en-ringen/

Zie de officiele NASA site https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/ voor het laatste nieuws over de missie | Gewijzigd: 26 april 2017, 14:49 uur, door Justin

PHOTOS: NASA's Cassini Probe Just Got Closer to Saturn Than Ever Before

NASA/JPL

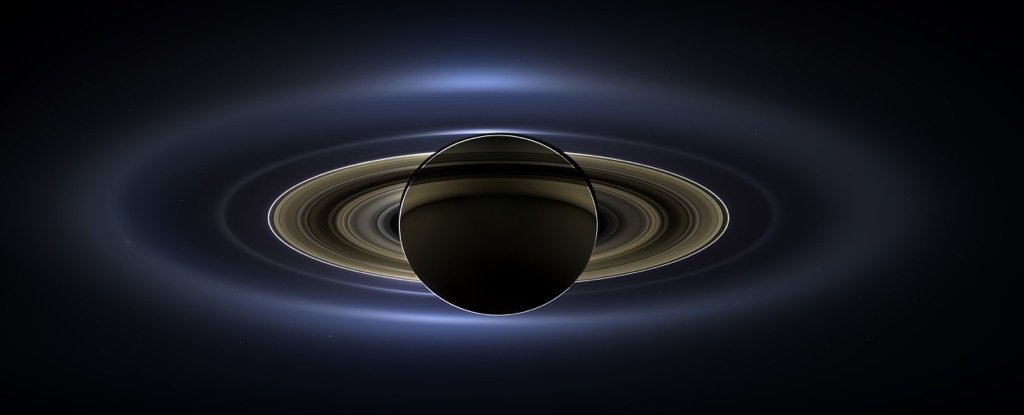

NASA's Cassini probe is plunging to its death. The nuclear-powered spacecraft has orbited Saturn for 13 years, and sent back hundreds of thousands of images.

The photos include close-ups of the gaseous giant, its famous rings, and its enigmatic moons - including Titan, which has its own atmosphere, and icy Enceladus, which has a subsurface ocean that could conceivably harbour microbial life.

To prevent Cassini from crashing into and contaminating any of those hidden oceans, the space agency has directed the craft, which is running out of fuel, onto a crash course with Saturn.

On Monday, the space probe conducted the first of its final five orbits around the planet, dipping into Saturn's atmosphere, according to NASA. It's all part of the "Grand Finale" for the US$3.26-billion, 20-year mission, which will end on September 15 as the spacecraft dives to its demise and burns up like a meteor.

"As it makes these five dips into Saturn, followed by its final plunge, Cassini will become the first Saturn atmospheric probe," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL, said in a press release.

"It's long been a goal in planetary exploration to send a dedicated probe into the atmosphere of Saturn, and we're laying the groundwork for future exploration with this first foray."

These last passes will reveal new data about Saturn, its atmosphere and clouds, the materials making up its rings, and the mysterious gravity and magnetic fieldsof the gas planet.

"It's Cassini's blaze of glory," Spilker previously told Business Insider. "It will be doing science until the very last second."

Here's what the probe's final spiral is revealing so far.

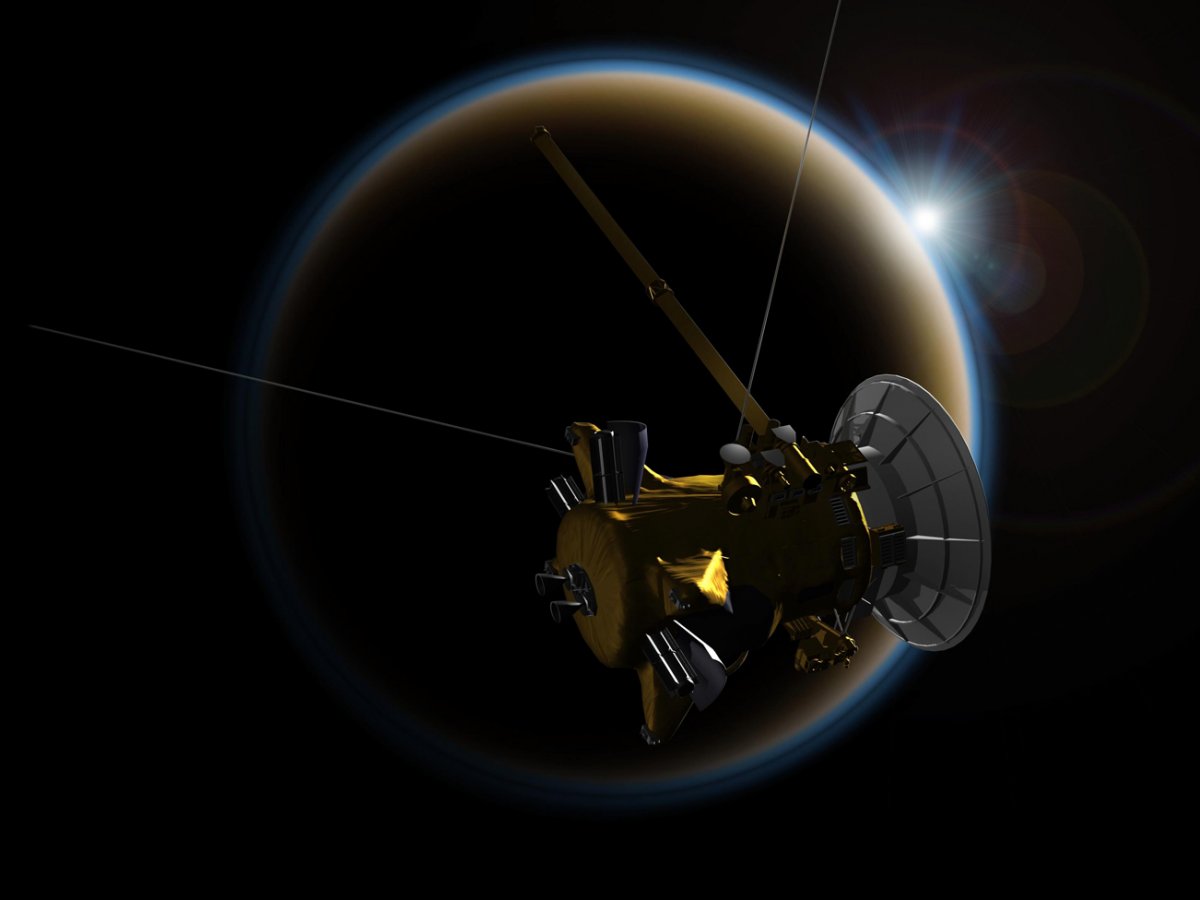

Gravity from Titan, Saturn's planet-sized moon, plays a key role in Cassini's final orbits. NASA is using the force to bend Cassini's course, a task that would otherwise require large amounts of fuel.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Above is an artist rendering of NASA's Cassini spacecraft observing a sunset through the hazy atmosphere of Titan, Saturn's largest moon.

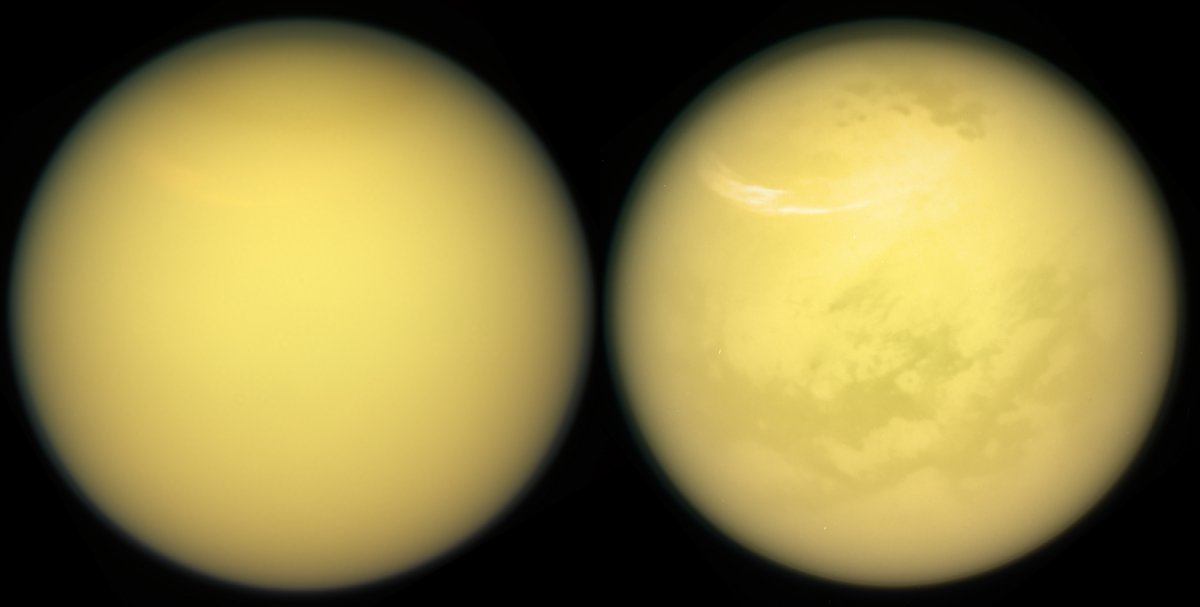

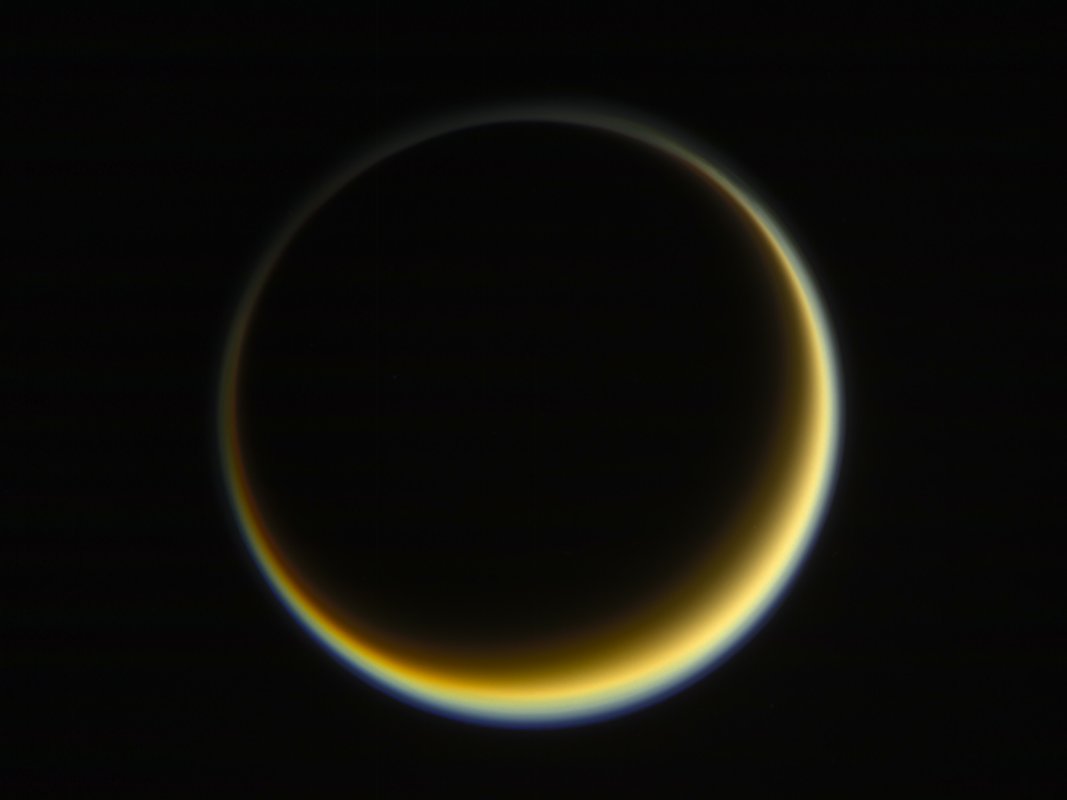

These two views of Titan show the new details about the moon's surface - including clouds and hazes in its atmosphere - that Cassini has revealed:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

They were acquired on March 21, 2017, and published by NASA on August 11.

The first of the probe's final five orbits took it between the rings and the planet itself. Data from that fly-by is being sent back to NASA today.

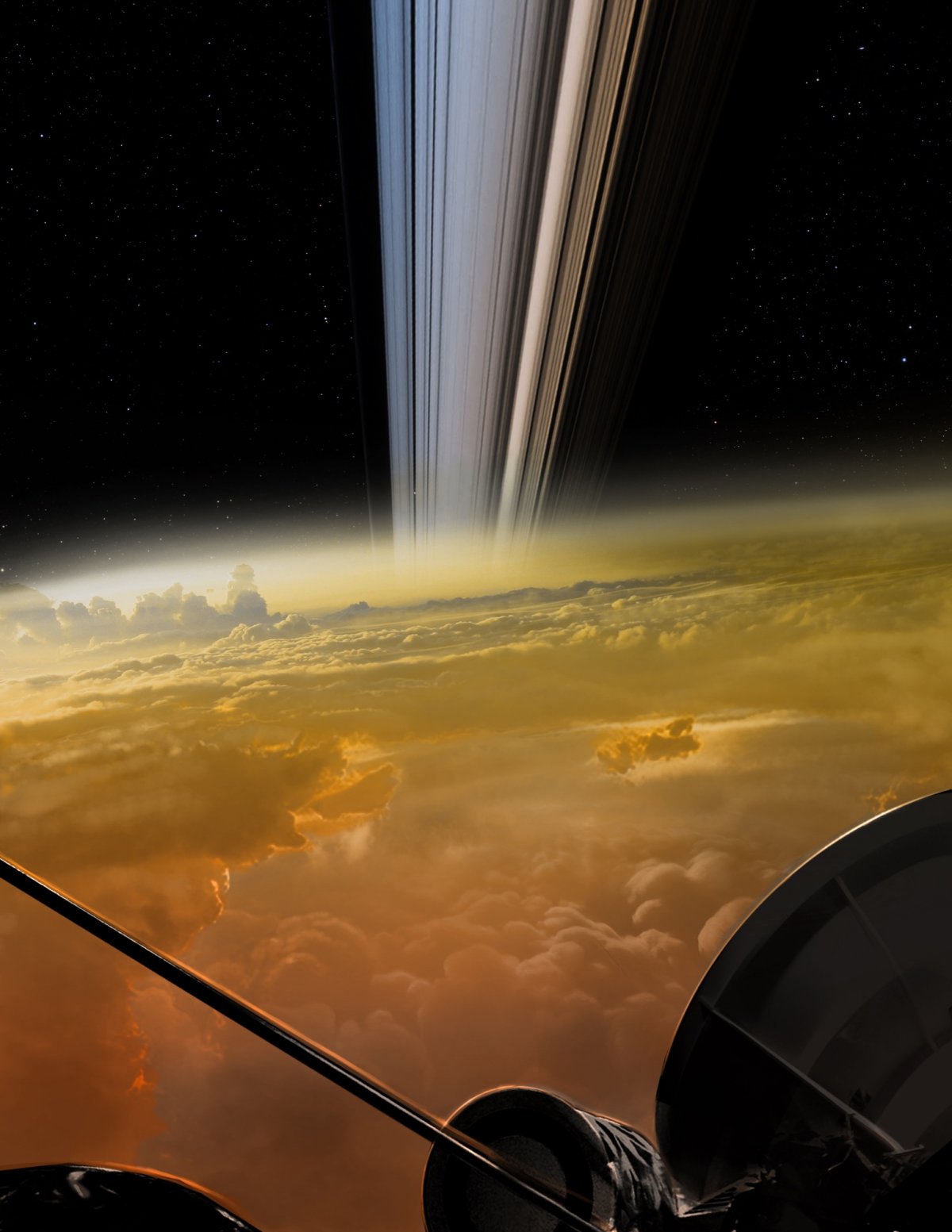

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Above is an artist's view of what Cassini might see during its final plunge into the clouds of Saturn.

NASA hopes this closest-ever brush with Saturn will reveal new components of its atmosphere, which is believed to be about 75 percent hydrogen, with most of the rest being helium.

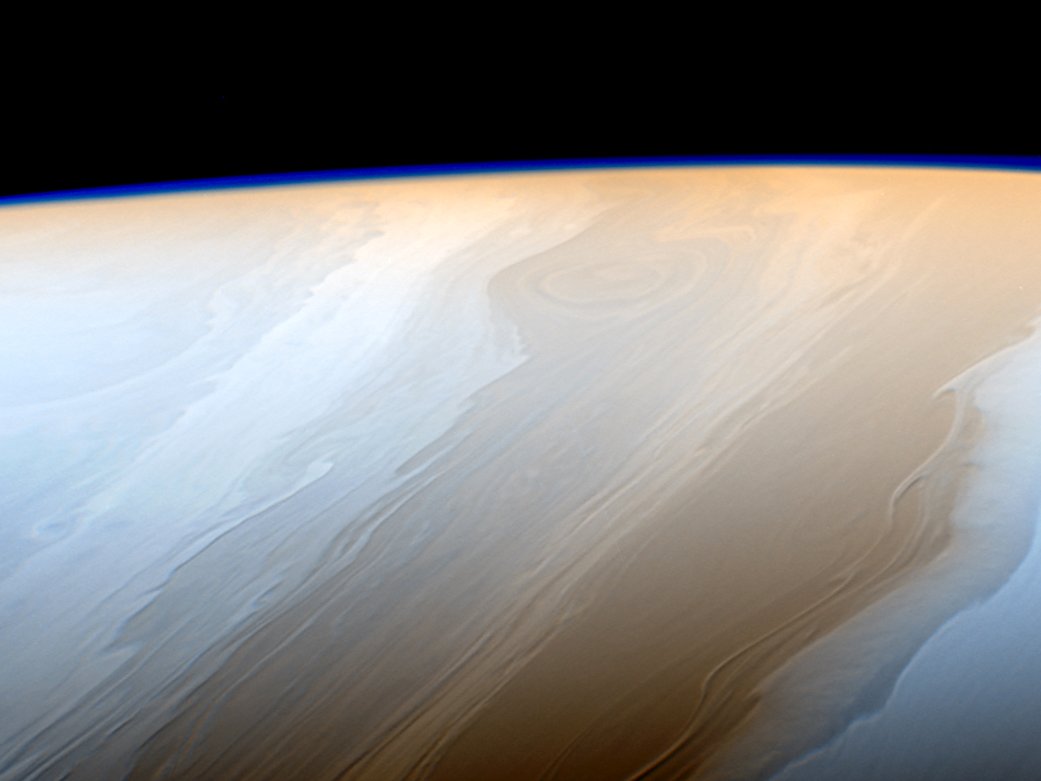

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The false-color image above was taken with Cassini's narrow-angle camera on May 18, 2017, from a distance of approximately 750,000 miles (1.2 million kilometres).

The clouds on Saturn look like strokes from a cosmic brush because of the wavy way that fluids interact in Saturn's atmosphere.

So far, scientists have been unable to discern any tilt between Saturn's magnetic field and its rotation axis. That contradicts our understanding of magnetic fields, and makes it impossible to know exactly how long Saturn's days are.

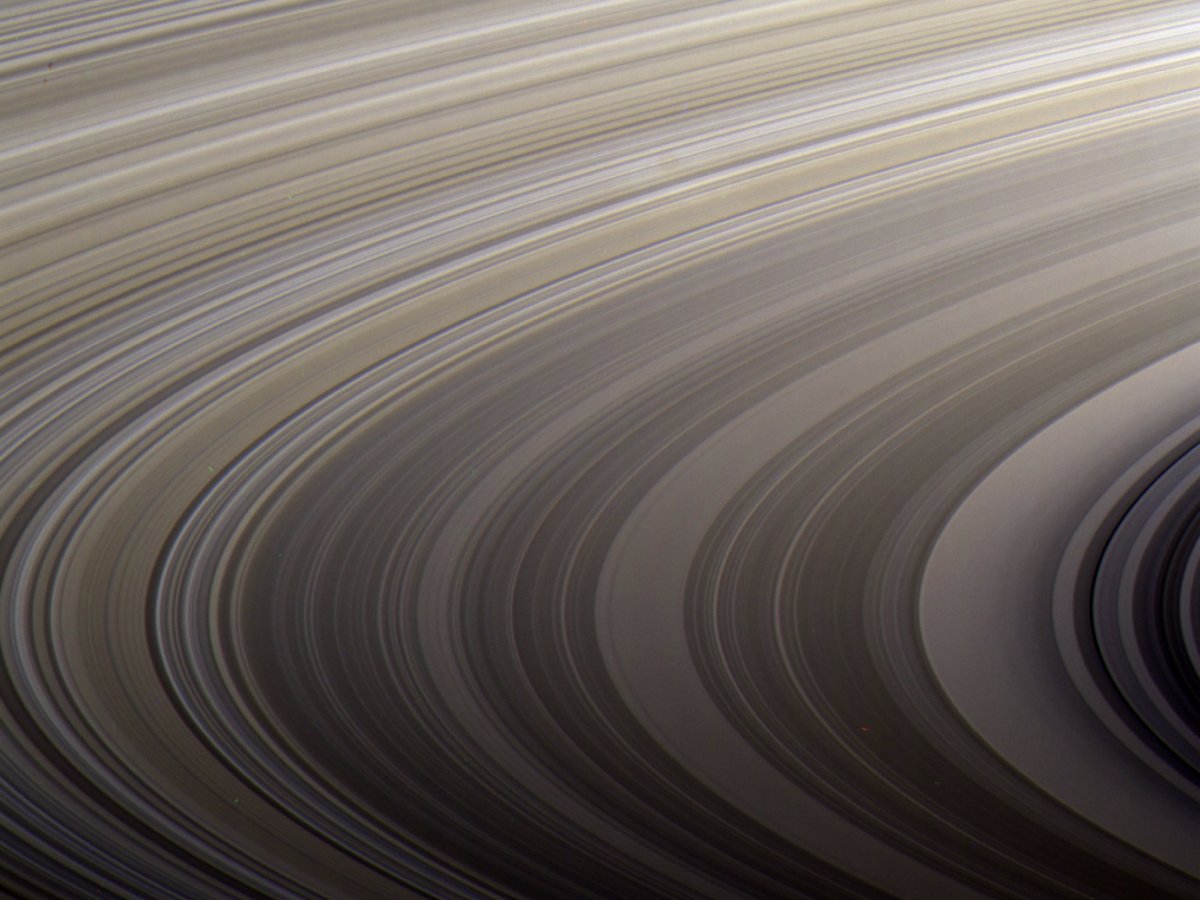

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI/Kevin M. Gill

This is a close-up of the rings of Saturn as seen by Cassini.

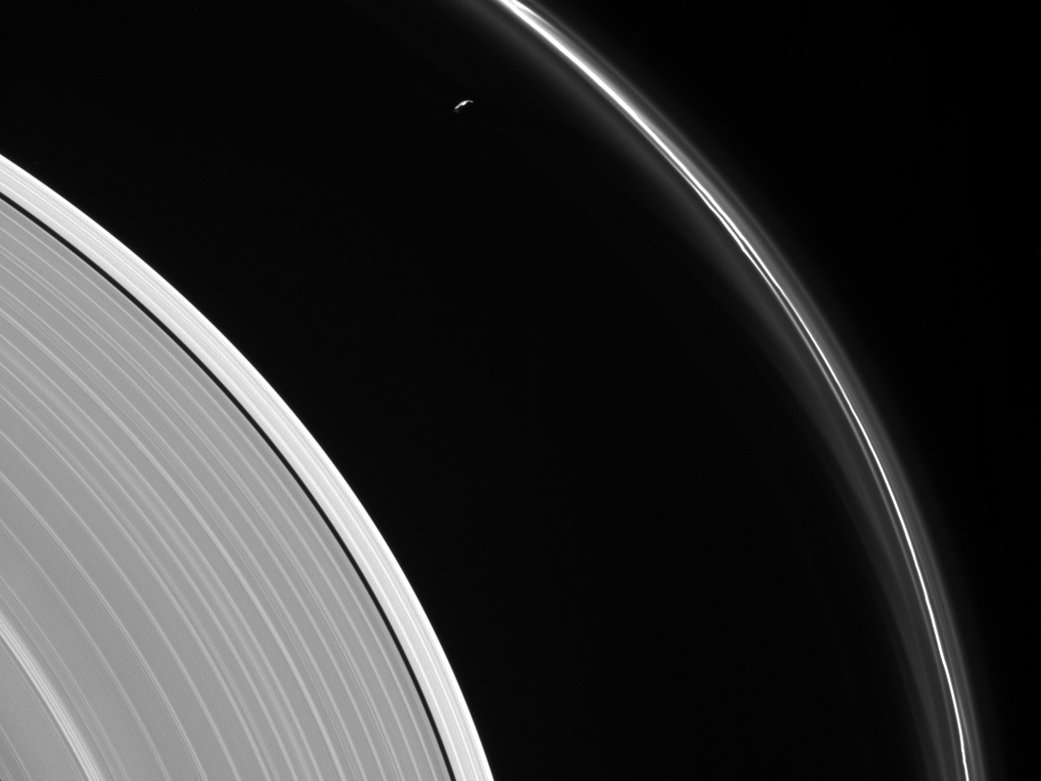

Before getting to the Grand Finale stage, Cassini was able to capture this view of Saturn's moon Prometheus inside Saturn's F ring:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The Cassini spacecraft used its narrow-angle camera to take this image using visible light on May 13, 2017.

Many of the narrow F ring's faint and wispy features result from its gravitational interactions with Prometheus, which is 53 miles (86 kilometres) across.

On its next dip into Saturn's atmosphere on August 20, Cassini may be able to go even deeper. It could see the planet's northern aurora and measure the temperature of Saturn's southern polar vortex.

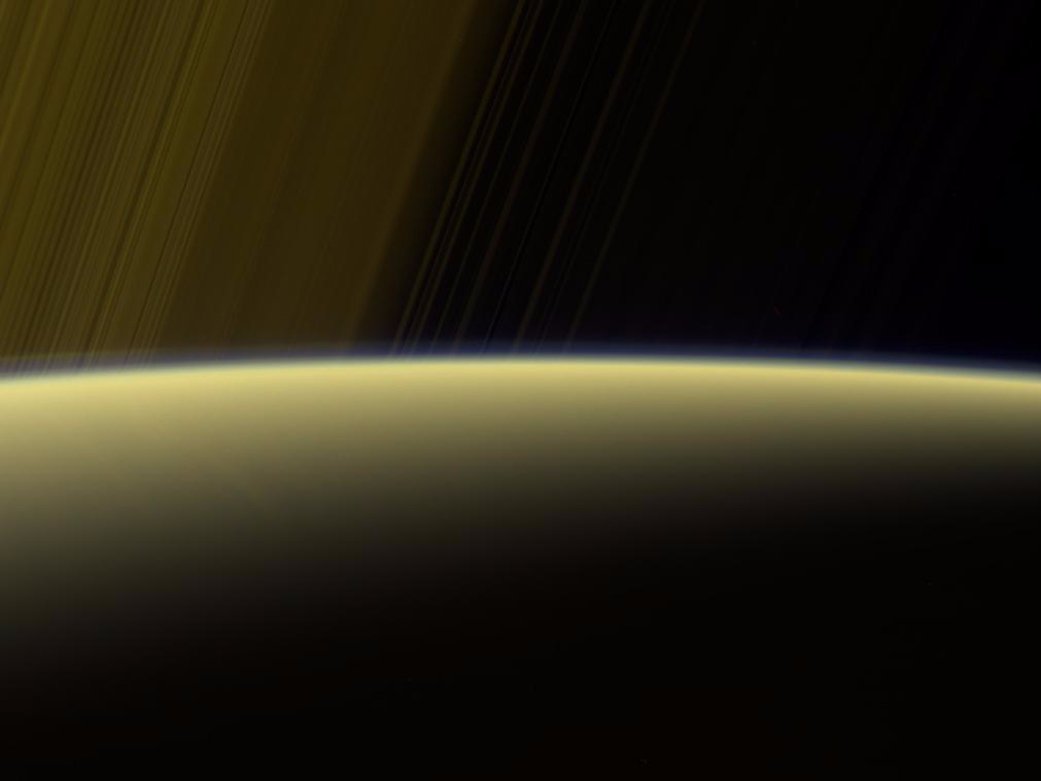

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The view above is a false-color composite made using images taken in red, green and ultraviolet spectral filters. The images were obtained using Cassini's narrow-angle camera on July 16, 2017, at a distance of about 777,000 miles (1.25 million km).

To capture the image above, Cassini gazed toward the rings beyond Saturn's sunlit horizon. Along the limb (the planet's edge) at left can be seen a thin, detached haze. This haze vanishes toward the right side of the scene.

On its last dives through the rings, Cassini will also be able to analyse samples of Saturn's rings on its last dives. That will help scientists figure out how dense they are and better understand what they're made of.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Cassini's wide-angle camera took the image above on Feb. 25, 2017.

In the photo, the light of a new day on Saturn illuminates the planet's wavy cloud patterns and the smooth arcs of its vast rings. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 10 degrees above their plane.

Cassini will need to use Titan's gravity again on September 11 to help direct its final plunge, which will happen on September 15.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The Cassini spacecraft's narrow-angle camera captured this image of Titan on May 29, 2017.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft looks toward the night side of Saturn's moon Titan in a view that highlights the extended, hazy nature of the moon's atmosphere. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometres) from Titan.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

Bron: http://www.sciencealert.com/photos-nasa-s-cassini-probe-just-got-closer-to-saturn-than-ever-before

De laatste week is aangebroken voor Cassini

End of Mission Timeline

On the final orbit, Cassini will plunge into Saturn fighting to keep its antenna pointed at Earth as it transmits its farewell. In the skies of Saturn, the journey ends, as Cassini becomes part of the planet itself. Watch the full video here.On Sept. 15, 2017, the Cassini spacecraft will make a fateful plunge into Saturn's atmosphere, ending the mission just one month shy of its 20th launch anniversary.Projected Times

Because Saturn is so far from Earth, Cassini will have been gone for about 83 minutes by the time its final signal reaches the Deep Space Network's Canberra station in Australia on Sept. 15, 2017.The current predicted time for loss of signal on Earth is 4:55 a.m. PDT (7:55 a.m. EDT) on Sept. 15, 2017. This time may change as Saturn's atmosphere slows Cassini during each of the final orbits.

Times in left column are spacecraft event time, i.e., when the events happen at Saturn. "ERT" (in right column for some entries) refers to Earth received time, which is the time when the spacecraft's signal relaying the event arrives on Earth. After events happen at Saturn, it takes 83 minutes for Cassini's radio signal to reach Earth.

All times are estimates and may change by a few minutes based on the density of Saturn's atmosphere as encountered by the spacecraft in its final five orbits.

Event happens at Saturn Signal received on Earth

Sept 8

8:09 pm EDT (5:09 pm PDT) Final dive through the gap between Saturn and the rings (closest approach to Saturn is 1,044 miles, 1,680 kilometers above the cloud tops)

Sept 9

9:07 am EDT (6:07 am PDT) Downlink of data from last Grand Finale dive begins 10:29 am EDT (7:29 am PDT)Sept 11

3:04 pm EDT (12:04 pm PDT) Final, distant Titan flyby (aka, the "goodbye kiss") closest approach (altitude 73,974 miles, 119,049 kilometers above Titan's surface)

Sept 12

1:27 am EDT (10:27 pm PDT - Sept. 11) Apoapse, or farthest point from Saturn in the orbit (800,000 miles, 1.3 million kilometers from Saturn) 7:56 pm EDT (4:56 pm PDT) Downlink of final Titan data begins

9:19 pm EDT (6:19 pm PDT)

Sept 14

3:58 pm EDT (12:58 pm PDT) Scheduled time when the final image will be taken by Cassini's cameras 4:22 pm EDT (1:22 pm PDT) Spacecraft turns antenna to Earth; communications pass begins for final playback from Cassini's data recorder, including final images. Communications link is continuous from now to end of mission (~14.5 hours) 5:45 pm EDT (2:45 pm PDT)

11:15 pm EDT (8:15 pm PDT) Deep Space Network station in Canberra, Australia, takes over tracking Cassini to end of mission

Sept 15

1:08 am EDT (10:08 pm PDT - Sept. 14) High above Saturn, Cassini crosses the orbital distance of Enceladus for the last time3:14 am EDT (12:14 am PDT) Spacecraft begins a 5-minute roll to point instrument (INMS) that will sample Saturn's atmosphere and reconfigures systems for real-time data transmission at 27 kilobits per second (3.4 kilobytes per second). Final, real-time relay of data begins 4:37 am EDT 1:37 am PDT

3:22 am EDT (12:22 am PDT) High above Saturn, Cassini crosses the orbital distance of the F ring (outermost of the main rings) for the last time

6:31 am EDT (3:31 am PDT) Atmospheric entry begins; thrusters firing at 10% of capacity 7:54 am EDT (4:54 am PDT)

6:32 am EDT (3:32 am PDT) Thrusters at 100% of capacity; high-gain antenna begins to point away from Earth, leading to loss of signal 7:55 am EDT (4:55 am PDT)

Pinpointing a Moment

As Cassini heads for its Sept. 15 plunge into Saturn, the mission team will continue to update their predicted time for loss of signal. This is the predicted time during Cassini's dive into Saturn when the spacecraft is expected to begin tumbling due to increasing atmospheric density, permanently severing the spacecraft's radio link with Earth. At this point the spacecraft's mission is over.

The predicted time for loss of signal changes because of effects from Saturn's atmosphere on each of the spacecraft’s final five orbits. On these passes, Cassini dips briefly into Saturn’s upper atmosphere, which causes drag. This drag alters Cassini’s velocity, which in turn affects when the spacecraft will reach Saturn’s atmosphere on the mission’s final day. More drag makes the spacecraft slow down in its orbit, which can move the end-of-mission time slightly earlier, by seconds or even minutes. The time could move forward slightly if the atmosphere turns out to be less dense than expected based on the previous passes.

Cassini’s flight team reviews the trajectory after each pass to see how the spacecraft's course was affected by the atmosphere. They use the new information to update their prediction of how the remaining passes will further alter the trajectory, and from these predictions they generate an updated time for loss of signal.

Bron: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/grand-finale/cassini-end-of-mission-timeline/

Cassini's Final Moments May Be Visible From a Telescope Here on Earth

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SSI

Early Friday morning (US time), NASA's Cassini probe will meet its doom as it becomes a streak of plutonium-laced fireworks in the clouds of Saturn.

The nuclear-powered robot was launched in 1997 to deeply study Saturn and its mysterious collection of moons. Cassini arrived in 2004, dropped off a lander on one moon, and has orbited Saturn and beamed back data and images to Earth ever since.

Scientists would love to keep the US$3.26 billion mission going, but their robot has gotten too low on propellant to safely control.

Extending the mission would risk crashing Cassini - which is contaminated with trace amounts of earthly bacteria - into Enceladus or Titan. These two moons of Saturn hide oceans of water and may be habitable to or even host alien life.

Instead of chucking the probe into deep space, like the twin Voyager spacecraft, NASA decided to destroy Cassini by sending it on a months-long death spiral into Saturn.

This daring manoeuvre - what NASA calls "the Grand Finale" - gave Cassini 22 unprecedented dives between Saturn and its gossamer-thin rings.

As NASA prepares to lose one of its most storied space probes, many space enthusiasts are wondering whether Cassini's final moments will be visible from Earth, 930 million miles away.

Business Insider posed that question to Linda Spilker, a Cassini project scientist and a planetary scientist at NASA JPL. Her answer: "It's gonna be tough, but I'm hopeful."

Why it will be so difficult to see Cassini burn up

When Cassini plunges into Saturn's outer atmosphere at about 76,000 mph, it should produce bursts of light. But that will be tough to see from Earth for a few reasons.

First, the brightest parts of those bursts will be in ultraviolet - the same wavelength of light that can cause sunburn. Because Earth's ozone layer soaks up gobs of ultraviolet light, however, any UV flashes will appear dramatically dimmed to anyone watching from the ground.

Another challenge is that Cassini's two nexuses of control - NASA and the European Space Agency - won't "see" the event in the dark of night, making the signal all the much dimmer as western telescopes fight twilight.

"There are really no big assets that we could be to bear either in the United States or in Europe to look," Spilker told Business Insider. "It's going to be five in the morning here, and of course even later in the day in Europe."

Because of those factors, Spilker said this moment in space history won't be like seeing the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet wallop Jupiter in 1994.

"Those objects were so much bigger and so much more massive than Cassini, and a lot of those strikes were on the night side. We've got sort of the double-whammy of a little tiny spacecraft that's really not that massive hitting on basically the day side of Saturn," Spilker said. "So it's unlikely, but it's definitely worth looking."

Space is the ideal place to record Cassini's fiery death, since the sun and Earth's atmosphere wouldn't be in the way. So, the Cassini mission asked NASA to use the Hubble Space Telescope to stare down Saturn for signs of a flash.

This could have worked, but Spilker said a recent discovery at Saturn led to a poor "luck of the draw" with Hubble.

During Cassini's last handful of dives between Saturn and its rings, the probe revealed that the planet's outer atmosphere extends farther than previously thought.

Ploughing through those sparse gases gradually slowed down Cassini - and this, in turn, bumped up the probe's time of death by about 15 to 20 minutes, Spilker said.

"It's really just in the last few weeks that we've started to get a better handle on what that time of impact would be," Spilker said.

When NASA studied this new timing, it realised Cassini would burn up while Hubble is flying over Earth's South Atlantic anomaly - a chink in the armour of our planet's protective shield where radiation levels and electric currents spike.

"We were trying to get some time on Hubble, but it looks like … the instrument we want to use will have to be turned off when we're flying across that region," Spilker said. "You don't want to have currents flowing at high voltage. You worry about damage to your instruments, so the best thing you can do is turn off high voltage."

She added: "I was sad to lose Hubble, because above [Earth's] atmosphere looking in the ultraviolet, that was a good chance. And it just didn't work."

Southern astronomers to the rescue?

But Spilker thinks all hope is not lost.

She said there's a chance that professional, ground-based telescopes in the southern hemisphere - perhaps those in Australia or Taiwan - might be sensitive enough and in the right place to record Cassini's death.

She also said there's a large community of space fans with powerful telescopes and refined techniques sprinkled across the globe that could help.

"There's still some really great, really capable amateur ground astronomers, in particular, that have returned some beautiful images of Saturn," Spilker said, reiterating that it will be a "tough one" to capture.

"Maybe the last of the fuel tank will suddenly brighten and we'll be able to see that. I think it's definitely worth looking," she said. "We might be surprised."

Bron: http://www.sciencealert.com/cassini-grand-finale-2017-nasa-farewell-hubble-can-we-see-it

Cassini-missie maakt zich op voor grote finale

Cassini-missie maakt zich op voor grote finale