Hij is "koud", maar er zijn aardbevingszwermen aan de gang

https://encrypted-tbn1.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTj_-QQ47nKR7w1qW9Hm08fBOQTjs6B06r7tewlZqT1UC-FcUDZyQ

De eruptie van 18 mei 1980:

De eruptie van Mount St Helens op 18 mei 1980, was een zeer spektaculaire uitbarsting, aangezien deze uitbarsting zijwaarts ging en een groot stuk van de berg naar beneden kwam. Hij is nu 400 meter lager dan de oorspronkelijke 2950 meter die hij had.Helaas was het ook de dodelijkste uitbarsting in de geschiedenis van de VS.

Bij de uitbarsting kwamen 57 personen om het leven en raakten 200 huizen, 47 bruggen, 24 km spoorweg en 300 km weg vernield. De uitbarsting werd voorafgegaan door een beving van 5,1 op de schaal van Richter.

De hoeveelheid energie die vrijkwam bij de grote uitbarsting van 1980 was vergelijkbaar met honderdvijftigmaal de kracht van de atoombom op Hiroshima. Voordat de eigenlijke eruptie plaatsvond steeg een enorme pliniaanse wolk uit de kratermond. De uitbarsting kreeg als explosiviteit een VEI van 5.

Een grote pyroclastische wolk (gloedwolk), met een temperatuur van rond de 500 graden Celsius, verwoestte alles op zijn weg naar beneden. Er ontstond een flinke krater (caldera). Tot in de wijde omtrek werden de bomen platgegooid en de omgeving werd "gezandstraald" over een oppervlak van ca. 600 km². Onbeschermde personen die door deze pyroclastische stroom werden overvallen werden binnen enkele tellen levend gekookt. Als de vulkaan niet in een zeer dunbevolkt gebied was gelegen had het aantal slachtoffers vele malen hoger kunnen zijn. De vulkaan was al lang niet meer actief geweest, sinds zijn 'ontdekking' in de 18e eeuw noteerde men enkel wat kleinere uitbarstingen.

In de maanden voor de uitbarsting werd de berg al in de gaten gehouden door de United States Geological Survey (USGS) en werden er mensen geëvacueerd. Op de ochtend van 18 mei 1980 rapporteerde David A. Johnston, een vulkanoloog bij de USGS, als eerste dat de uitbarsting was begonnen. Enkele tientallen seconden later werd hij op zijn veilig geachte observatiepost op 10 km afstand gedood door de pyroclastische wolk.

In september 2004 begon de berg opnieuw te roken, maar een grote uitbarsting bleef achterwege. Op 8 maart 2005 stootte de vulkaan een ruim 10 kilometer hoge wolk van as en stoom uit, waarna een lichte aardbeving volgde met een kracht van 2,5 op de schaal van Richter. De rookwolk, die ongeveer een half uur aanhield, was vanuit de wijde omtrek zichtbaar.

Bron: https://nl.wikipedia.org

Voor degenen "die er toen nog niet waren" of het geheel gemist hebben, hier een terugblik:

Mount st Helens, vandaag de dag:

Mount St. Helens is a cold-hearted volcano

Below most volcanoes, Earth packs some serious deep heat. Mount St. Helens is a standout exception, suggests a new study. Cold rock lurks under this active Washington volcano.

Using data from a seismic survey (that included setting off 23 explosions around the volcano), Steven Hansen, a geophysicist at the University of New Mexico, peeked 40 kilometers under Mount St. Helens. That’s where the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate melts as it sinks into the hot mantle beneath the North American plate, fueling an arc of volcanoes that line up like lights on a runway. All except for Mount St. Helens, which stands apart about 50 kilometers to the west. Still, Hansen and colleagues expected to see a heat source under Mount St. Helens, as seen at other volcanoes.

Instead, thermal modeling revealed a wedge of a rock called serpentinite that’s too cool to be a volcano’s source of heat, the researchers report November 1 in Nature Communications. “This hasn't really been seen below any active arc volcanoes before,” Hansen says.

This odd discovery helps show what the local crust-mantle boundary looks like, but raises another burning question: Where is Mount St. Helens’ heat source? Somewhere to the east, suggests Hansen. Exactly where, or how it reaches the volcano, remains a cold case.

Bron: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/mount-st-helens-cold-hearted-volcano

Mount St. Helens shakes 120 times within a week

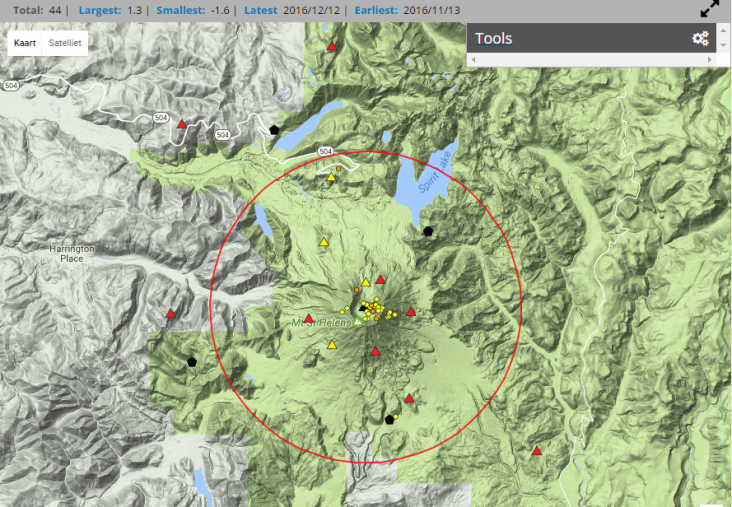

In less than a week, four swarms of more than 120 earthquakes shook Mount St. Helens in late November. Although they were too small to be felt even by someone standing directly over their epicenters, scientists say they reveal the volcano is likely recharging.

“Each of these little earthquakes is a clue and a reminder we are marching toward an eruption someday,” said Weston Thelen, a U.S. Geological Survey seismologist with the Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver.

However, “there’s nothing in this little modest seismicity, and none since 2008, that is a really good indicator of when that eruption will be.”

The earthquakes occurred between 1 and 2 miles below the surface and most registered at magnitudes of 0.3 or less; the largest was a magnitude 0.5. While the quakes are too small for human perception, scientists are able to study them thanks to sensitive seismometers stationed around the mountain.

As magma comes into the volcano’s system and is stored, scientists think that it releases gases and fluids that travel up into cracks, pressurizing and lubricating them, and causing small quakes.

“We know Mount St. Helens is slowly repressurizing. We can’t see it, but we think it’s inflating subtly,” said Liz Westby, a Cascades Volcano Observatory geologist.

Indeed, USGS scientists haven’t detected any anomalous gases or increases in ground inflation since the earthquake swarm.

“St. Helens is a well-behaved volcano, as far as we can tell,” Thelen said.

Westby said researchers have seen these kinds of earthquake swarms before.

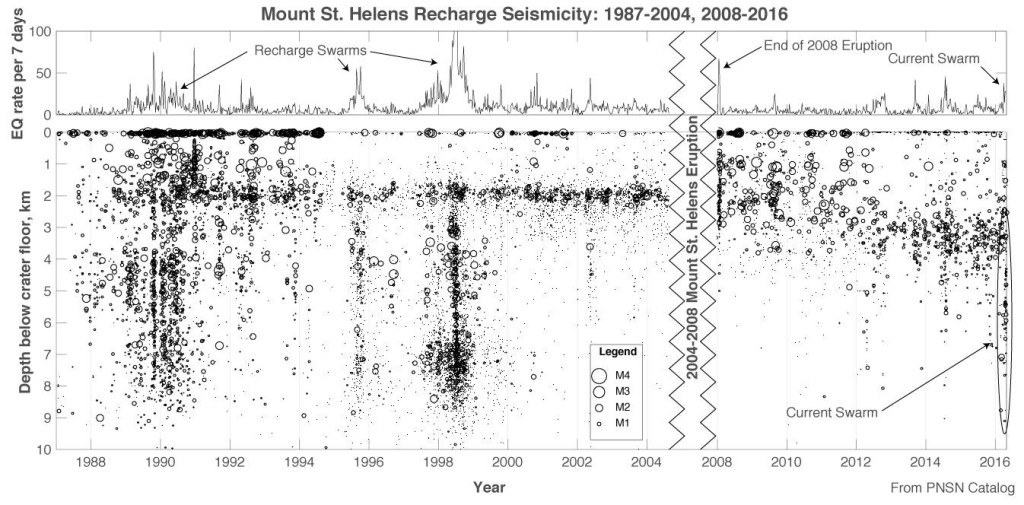

Similar seismic episodes occurred during recharge periods between 1986 and the 2004 eruption; the small earthquake clusters resumed shortly after the eruption ended in 2008 and have continued periodically. Most recently, swarm earthquakes were detected in March through May of this year.

Scientists don’t exactly know how the volcano’s plumbing is laid out, but the little earthquake clusters give them a slightly clearer picture of what’s happening beneath the surface. By measuring how the speed of the seismic waves change as they move through the earth, researchers can better understand rock densities and where magma chambers are.

“These quakes don’t happen very often; you have to really exploit the ones we do get,” Westby said. “(It) gives us a better understanding of what’s going on and tells us where we need to do more research.”

Bron: http://www.columbian.com/news/2016/dec/12/mount-st-helens-shakes-120-times-within-a-week/

Actuele registraties:

https://www.pnsn.org/volcanoes/mount-st-helens

Since the beginning of 2016, a swarm of small earthquakes has been occurring at under the volcano, suggesting that another phase of magma recharge is currently taking place.

The recorded quakes have been at shallow depths between 2-7 km under the summit and ranged in magnitudes from 0 (or less) to 3 on the Richter scale, i.e. they are all tiny. Only rarely, they exceeded magnitude 2 and only a very few might have been felt by persons being very close.

USGS volcanologists and seismologists interpret the vertical area where these quakes occurred as the area where a small amount of fresh magma has been rising into the volcano's plumbing system (a magma chamber). Magma rises, pressurizes surrounding rock to make space and causes fracturing = tiny quakes.

The current swarm is only one of a series of similar swarms that have taken place since 1988, including some much more energetic ones (such as during 1998-99). Most such earthquake swarms, not only at Mt. St. Helens, but at almost any volcano, are NOT followed by eruption, or at least not immediately. In the case of Mt. St. Helens, the large earthquake swarm during 1998-99 preceded the small effusive activity during 2004-2008 by 5 years.

For the time being, USGS keeps the volcano at alert level green (=normal); the observed seismic activity is too small to justify a raise in alert and is best seen as part of the normal activity during a dormant phase of the volcano. When the volcano will erupt again (it is almost certain that it will), is impossible to predict on the basis of these quakes alone. It might be years or even centuries.

Tot slot:

Er zijn dus nog wat vraagtekens romdom de "hittebron" van Mount St. Helens, aangezien deze 50 km ten westen van de vulkanische boog ligt.Dat er zich wat aan het opbouwen is, blijkt uit de aardbevingzwermen die er plaatsvinden. De bevingen zijn nog erg licht, maar is dus wel een teken dat magma zich naar boven "wringt", wat deze schokjes teweeg brengt. De kracht van de bevingen zijn niet krachtig, waardoor men zich vooralsnog geen zorgen hoeft te maken, dat er op korte termijn weer een uitbarsting komt. Dit kan nog jaren duren.

OnweerOnline/Joyce

Mount St. Helens, toen en nu

Mount St. Helens, toen en nu